This is an archive of the original TweakGuides website, with post-archival notes added in purple text. See here for more details.

Hardware Confusion 2019

[Page 2] The Old & The New

Welcome. It's been 10 years since the last Hardware Confusion article, so I have a lot of ground to cover, and many findings, ideas and tips I want to share with you on a range of topics. Let's get busy!

Post-Mortem of a Ten Year Old System

I bet you're wondering: "Ten years with the same system - couldn't you upgrade more frequently than that?"

Here's the thing, for the first six years or so, between 2009 and 2015, my system was powering along, seemingly unstoppable for everything including high-end gaming. For example, take a look at the range of videos I uploaded to my YouTube Channel on a regular basis during that time, demonstrating smooth gameplay at 1920x1200 resolution (1200p), often with maximum or near-maximum settings, on some system-crushing games of the period. Sure, the framerates weren't necessarily as high as gamers have come to demand these days - and they're even lower in the videos because I was using FRAPS to record full-frame uncompressed HD video onto the same drive I was playing the game on - but they were plenty smooth enough to give me lots of enjoyment and immersive eye candy.

A major reason for this was because I did upgrade my system, but only the most important component for gaming: the graphics card (GPU). I went from a GTX 285 in January 2009 to a GTX 480 in 2010, then to a GTX 580 in late 2011, and finally, to the GTX 970 at the end of 2014; a new GPU roughly every two years. Note: I was working with Nvidia from 2010 to 2013 writing game guides for GeForce.com, so two of these GPU upgrades were provided by Nvidia for free.

That's an important lesson if you're a gamer: work with Nvidia so you can get free GPUs. Just kidding, the lesson is to always focus on the graphics card. Upgrading the CPU, the RAM, and/or the motherboard will likely yield minimal benefit relative to the significant FPS increase and improved graphics capabilities that a new GPU brings with it. The reason is simple - at higher resolutions, and with more complex graphical effects, the rest of your system is acting primarily as a glorified data pipeline to the GPU, which is doing the bulk of the work. As long as your storage is reasonably fast (see below), and your CPU and motherboard aren't from the dawn of time, a new GPU is all a gamer really needs to experience a major system refresh.

Another significant upgrade I undertook in 2012 was to replace my then still-fast, but mechanically limited, 10,000RPM WD Velociraptor hard drive, with a 240GB Intel 520 series SSD. I immediately felt the greatly improved responsiveness in a range of tasks. Once again, for an increase in almost all areas of performance on your PC, look to the latest forms of storage technology. Think of it this way, a computer is like a high-performance car engine fuelled by data. Your storage drive(s) are like the gas tanks holding this fuel, and the information pathways on your motherboard, known as Buses, are like fuel lines. Newer forms of storage not only hold more data, they can access it far more quickly and utilize bigger pipelines to get more of it to where it's needed in a hurry, preventing the stuttering and slowdowns that can occur when slower forms of storage struggle to keep the engine consistently fed.

By the tail end of 2015, I was no longer actively gaming, and so my primary motivation to continue upgrading my GPU, and my system in general, had declined. For the last few years of its life, the system received only a few minor upgrades: a new wireless keyboard and mouse combo, a new router and a Wi-Fi card. But even some of these opened up new avenues of performance and enjoyment, which I'll discuss.

In 2018, with my system entering the twilight of its life, I honestly didn't feel as though things were getting so bad as to require a full upgrade. For most of my daily tasks, it seemed reasonably responsive, and certainly reliable enough.

The Old System

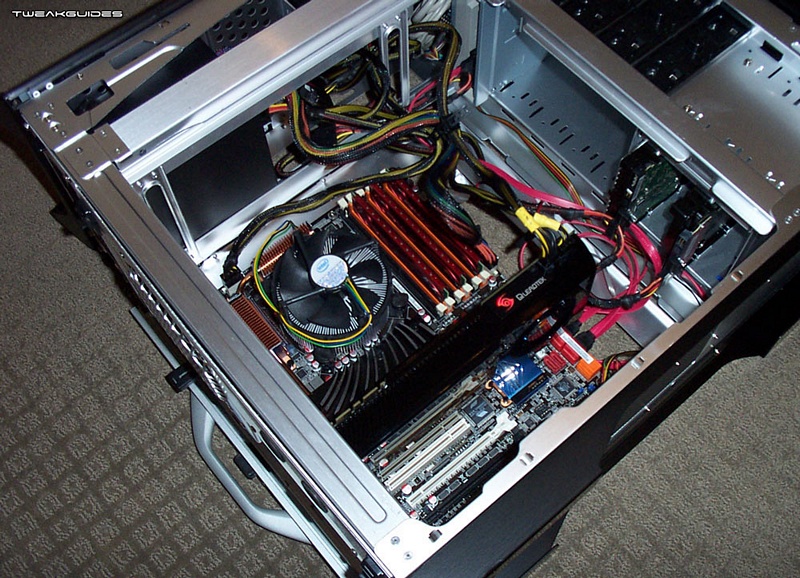

Built on a foundation of components first assembled with loving care in January 2009, at the end of 2018 my old system looked like this:

CPU: Intel Core i7 920 2.66GHz

CPU Cooling: Stock Intel HS&F

Motherboard: ASUS P6T-Deluxe X58

RAM: 6GB (3 x 2GB) G.Skill 1333MHz DDR3

Graphics: EVGA GeForce GTX 970 SC 4GB

Sound: Onboard ADI AD2000B HD Audio Chipset

Monitor: 24" Samsung 2443BW LCD

Primary Drive: 240GB Intel 520 SSD

Network Drives: 8TB (2x2TB, 1x4TB) WD My Passport USB HDDs attached to router

Optical Drive: Pioneer BDR-205 Blu-Ray Writer SATA

Keyboard & Mouse: MS Wireless Desktop 3050

Power Supply: Seasonic M12 700W

Case: Cooler Master Stacker 832 SE

OS: Windows 10 Professional 64-bit

Network: ASUS RT-AC68U Router, ASUS PCE-AC56 PCI-E WiFi Adapter

Several components, including the graphics card and primary drive, had been updated since this machine was built in 2009. But the CPU and its cooler, the motherboard, RAM, monitor, power supply, and the case with all of its fans, would shortly celebrate their tenth birthday. Even the upgraded primary drive, an SSD purchased in 2012, was reaching 7 years of service and 500,000GB in writes.

While the system was performing reasonably well for non-gaming tasks, ten years in terms of the expected lifespan of consumer electronics components is a long time. I became worried that a key component, like the motherboard, CPU, SSD, or worst of all, the PSU, would fail and take my data with it, or in the case of the PSU blowing, may also take other components with it. Should I upgrade now, or wait for the system to die?

Interlude: Determining Reliability

If you've ever looked closely at the specifications for electronic components, you may have seen the term Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) and/or Mean Time To Failure (MTTF). Technically, these two things are not the same; MTBF refers to the average (mean) time between each repairable failure of a component, whereas MTTF is the average lifespan of a product up to the point where it can't be repaired. Either of these seems ideal as an indicator of reliability or durability, but not so. MTBF/MTTF are statistical averages, usually taken over a large number of a particular type of component, and they're often measured under controlled conditions.

For example, storage drives always provide an MTBF rating in their specs, but it's effectively meaningless if used as a measure of lifespan. The Intel 520 series SSD I installed in my system seven years ago, lists in its specifications a MTBF of 1,200,000 hours. That equates to 137 years of continuous operation before a (repairable) failure is likely to occur in my drive. And here I am, like a chump, thinking about replacing it, when it still has 130 years of flawless operation to go. Clearly this is a nonsense figure when applied to an individual drive. Intel couldn't possibly have tested this model for 137 actual continuous years of operation unless they had access to a time machine and set up a secret testing facility back in the late 1800s.

To correctly interpret MTBF, consider the fact that it's usually derived from a large sample. The only logical way to interpret the figure is that, on average, for every 1,200,000 hours of combined continuous operation of numerous Intel 520 SSDs, a single repairable fault was recorded. That's still pretty good, but not the same as saying each Intel 520 SSD is likely to last for 137 years on average, or anywhere near that figure, before a repairable fault will occur. Use MTBF figures with caution, and only as a very general indicator of relative quality, i.e.: when comparing two products of the same type, the one with the higher MTBF/MTTF should be better in terms of quality.

The manufacturer's warranty is probably a better indication of the actual expected lifespan of a product. In the case of my Intel 520 SSD, it had a 5 year warranty, which sounds far more plausible as an expected service life than 137 years, and given mine was already in its 7th year of operation, made me all the more nervous. SSDs will usually stop working without any warning signs, and often with little possibility of getting them operational again so that you can recover your data. Similarly, my Seasonic M12 700W PSU had a 5 year warranty, but I'd already used it for twice that amount of time, so this was another area of major concern, given power supplies can suddenly blow capacitor(s), damaging any components connected to them.

Interestingly, more recently some of the quality PSU suppliers like Seasonic have started extending their PSU warranties to 10 or even 12 years on certain models. No doubt my experience, and the lower warranty claims on certain models by a range of other customers, has made these companies bolder in asserting the quality of their wares. It's a good sign. However, companies often use a range of variables to determine warranty, and these aren't just restricted to quality or expected lifespan of a product. In some instances, it can benefit a company to provide lengthy warranty coverage despite known poor quality, because it bolsters consumer perceptions and can eventually translate into increased sales revenue that far outweighs the increased warranty claim costs. In the automotive world, Hyundai is well-known for employing this strategy.

Let's examine a specific warranty that seems too good to be true: EVGA has a program where, for between $30-$60 more, customers can extend the normal 3 year warranty on specific components such as GPUs by up to 5 or 10 years. How can this be viable? Firstly, EVGA already has a well-deserved reputation for quality, so the program serves to reinforce their already excellent reputation, netting them more sales. Secondly, it only applies to products that have the -KR code in their part number, and these are typically higher-quality enthusiast-level products anyway. Thirdly, and most importantly, EVGA specifies in their terms and conditions: "This Limited Warranty is only valid for the Original Purchaser" and "an EVGA Extended Warranty and/or EVGA Advanced RMA will not transfer to a second owner."

This is a critical clause: given the enthusiast-oriented products it applies to, and the generally fast obsolescence of PC gear, only a tiny fraction of original customers will likely still have, much less be actively using, that product five or ten years later, especially if it's a GPU. So paying extra to get an extended warranty on a product you probably won't be using when that warranty kicks in, which probably wasn't necessary anyway given its higher quality, or doesn't apply to you because you bought it second-hand, is not a great deal.

Always read the warranty conditions carefully, because some warranties are not worth the paper they're written on - this applies to both the original warranty, and particularly to extended warranties. A few more examples can help illustrate this point:

-

Some warranties have a requirement that the product be serviced regularly by an official dealer, otherwise the warranty is void. This can be argued as a necessity for technical reasons, but in reality, no matter what the consumer does, they will lose. If they service the product as frequently as recommended (typically way too often), they end up effectively paying for any replacement in hefty service fees; if the regular servicing actually helps extend the product's life, this reduces warranty claims at the consumer's expense; and given most consumers forget, ignore, use alternate repairers, or are unaware of the servicing requirement, it also gives the manufacturer a convenient out-clause if a claim is made.

- Requiring that the product be sent back to the manufacturer, sometimes thousands of miles away, at the customer's expense, for warranty or repair. This works like an insurance excess or deductible, it discourages most minor, and even some major, warranty claims. If you live in Australia for example, having to send a critical system component like a GPU to the US or Asia at a hefty price in postage, then having to wait 6-8 weeks or more to get it back, risking damage in transit to boot, results in some owners simply not bothering.

- Voiding warranty if a component has been overclocked or modified in any way, even to the point of not honoring warranties if a particular sticker seal on the product has been violated in any way. This would be fine except that some companies actively encourage overclocking by pushing lots of overclocking-friendly features, yet still penalize overclockers if they actually do what they're encouraged to do.

Refer to detailed lists of warranty types and conditions for your country to see the types of things to look out for. The following two apply to the US and Australia respectively: US Federal Trade Commission Consumer Information and Australian Consumer Law Warranty Information.

These caveats aside, the length of a manufacturer's warranty is generally a reasonable indication of the actual lifespan of a product, compared to more abstract figures such as MTBF/MTTF. In some countries, the advertised quality and the price you pay are also considered under local consumer law to be an indication of its expected longevity regardless of the manufacturer's warranty.

The New System

I live by the motto: Hope for the best, plan for the worst. On that basis, I made up my mind to upgrade to a new system as soon as possible, rather than just wait for my old system to die and risk data loss or catastrophic hardware failure. This is the system I assembled and first booted up on 11 January 2019.

CPU: Intel Core i7 9700K 3.6GHz

CPU Cooling: be quiet! Pure Rock CPU Cooler

Motherboard: ASUS Prime Z390-A Socket 1151

RAM: 32GB (2x16GB) Corsair Vengeance DDR4

Graphics: EVGA GeForce GTX 970 SC 4GB

Sound: Onboard Realtek ALC S1220A HD

Monitor: 24" Samsung 2443BW LCD

Primary Drive: 500GB Samsung 970 EVO M.2 NVMe SSD

Network Drives: 8TB (2x2TB, 1x4TB) WD My Passport USB HDDs attached to router

Optical Drive: Pioneer BDR-205 Blu-Ray Writer SATA

Keyboard & Mouse: MS Wireless Desktop 3050

Power Supply: Seasonic Focus Gold 650W

Case: Fractal Design Define R6 Black

OS: Windows 10 Professional 64-bit

Network: ASUS RT-AC68U Router, ASUS PCE-AC56 PCI-E WiFi Adapter

The components in italics are those that I eventually decided to carry over from the old system, either because they're still relatively new, are doing their chosen tasks extremely well, and/or if they die, will not damage anything else, so I can let them run to failure. As I write this, over a month after I first booted it up, I can confirm that it has been running extremely well with no issues whatsoever.

In the next section, I discuss my choices, including addressing the highly controversial Intel vs. AMD debate, I run through a few real-world benchmarks, and provide a whole heap of tips, tweaks and general advice based on everything I have learned while researching and optimizing this system.

Choosing Components

Back in 2009, I covered my general procedure for selecting hardware in the Hardware Confusion 2009 article, and it remains completely valid today, so I won't rehash it here. It's not rocket science. Put together a rough idea of your personal priorities, then do plenty of research, read reviews, and search for user feedback to ensure that you buy the gear best suited to your priorities while avoiding lemons. Like most things in life, the theory is fairly straightforward, it's putting it into practice that the hard part.

In terms of my priorities, they're not the same as what I wanted in 2009, which were, from highest to lowest: 1. Stability, 2. Longevity, 3. Noise, 4. Performance, 5. Price, and 6. Aesthetics. My priorities in 2019 are:

1. Stability: This is always my number one priority, and I strongly suggest that you make it yours too. It's totally pointless, not to mention very frustrating, to have a system that is unreliably random in its behavior, at any time, for any reason. As more and more of our lives are translated into digital form, it's also downright dangerous to trust your data to an unstable system.

2. Aesthetics: This took a big jump up the charts in my list of priorities. I want a mature, uniform, black business-like look to my PC and peripherals, and I want to be rid of any fancy LEDs, visible components, overly elaborate features, excessive cabling and so forth. I turn 50 soon, I need to start pretending I'm an adult!

3. Noise: Along with the mature aesthetics, I'm aiming for almost zero noticeable noise output. The previous system was fairly quiet due to a large open-flow case, stock air cooling, and as of 2014, a GPU that disables its fan when it's below 60C. But I figured I could do better.

4. Longevity: A high priority last time, and one which ultimately paid off, this time it's almost a given that these components will last longer regardless. Why? Three key reasons: 1. No longer a gamer, I don't have to upgrade as often to keep up; 2. I believe we've effectively hit a plateau in desktop computing power vs. the tasks that use it (gaming aside); and 3. I believe that even medium-end consumer-level components are built to last longer these days, resulting from a range of factors such as fewer moving parts, lower power usage, better built-in protections, etc.

5. Performance: Why is this so low on my list of my priorities? Remember, priorities are relative. I value performance more than the "average" PC user, just not as much as a high-end gamer or a serious overclocking enthusiast. So good performance is a must, but not at the expense of stability, aesthetics, noise, or longevity.

6. Price: I'm not a wealthy man, and this system was not cheap. But I firmly believe in the concept of false economy; cutting corners where it matters just results in a mediocre outcome at a moderate price, which to me is wasted money. This has always been the dilemma of the desktop PC in my opinion: either pay the bucks to build a decent system, or just purchase an inexpensive computing device such as a tablet, smartphone or a gaming console. When it comes to PCs, as Yoda would say: "Do. Or do not. There is no try."

The way I pictured it, I would be building a system that was similar to the one I had over the past ten years, but aside from obviously being faster, it would be more compact, sleek, mature and tasteful, and it would be almost undetectably silent the vast majority of the time. So off I went to do countless hours of intensive research. Well not exactly. This time around, complacency and a touch of arrogance meant that I thought I'd speed through the process. I read a few reviews to be sure, and the initial list of parts I put together in December 2018 was close to my final purchased system, but I made a couple of blunders, one of which would have been fairly major had I not followed some good advice given to me.

The major potential blunder I'm speaking of relates to the system's primary drive. The second near-blunder wasn't as major, but was still quite important due to my restructured priorities and had to do with the case. I'll discuss these in more detail later. "But wait!" you say, "What about your biggest blunder, the fact that you bought an Intel CPU!" Easy there tiger, I was aware of the fact that AMD has been taking significant steps to jump back to the top of the CPU market against rival Intel with its Zen-based Ryzen brand of CPUs. I also noted, and was frequently reminded by others, of the upcoming Ryzen 3000 series, AMD's next-gen 7nm CPUs that are supposed to be out soon.

That leads us nicely onto the next section, wherein we examine my hardware choices, starting with a long, detailed look at the core of any system: the CPU (and its cooling), the motherboard, and the RAM.

|

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.